ThereminGoat

Apr 21, 2023

•5 minutes

An Introductory Guide to Keyboard Switch Springs

When it comes to choosing mechanical keyboard switches, have you stopped to consider the type of spring used? In this guide, I cover common spring types.

Symmetric Long Switch Spring closeup

If switches are the heart of any good mechanical keyboard, then what exactly does that make springs? Completely disregarding the fact that I have no good answer to fill out that introductory analogy, I think a brief discussion about some of the types of springs you are likely to encounter in modern keyboard switches might be in order. While this is almost certainly not a strange topic to anyone who has looked into modifying their own switches or ‘frankenswitching’ before, many people who simply buy switches without ever opening them would be shocked to learn that there are some actual differences beyond just the marketing terms used to sell switches. Even though I make no promises as to how well this article will hold up in several years’ time given the rapid expansion in variety of springs offered in just the past year or two, it is still very much worthwhile to cover the basics of springs as they exist today. After all, a simple small change in just the weighting of the springs in your switches could have a bigger effect on how your keyboard feels and sounds more so than changing any other component around!

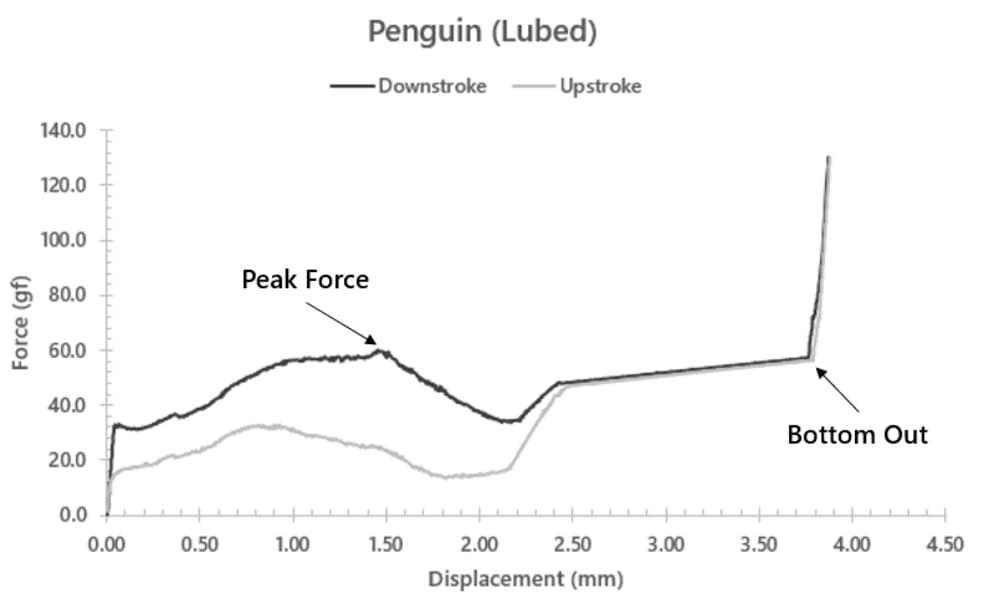

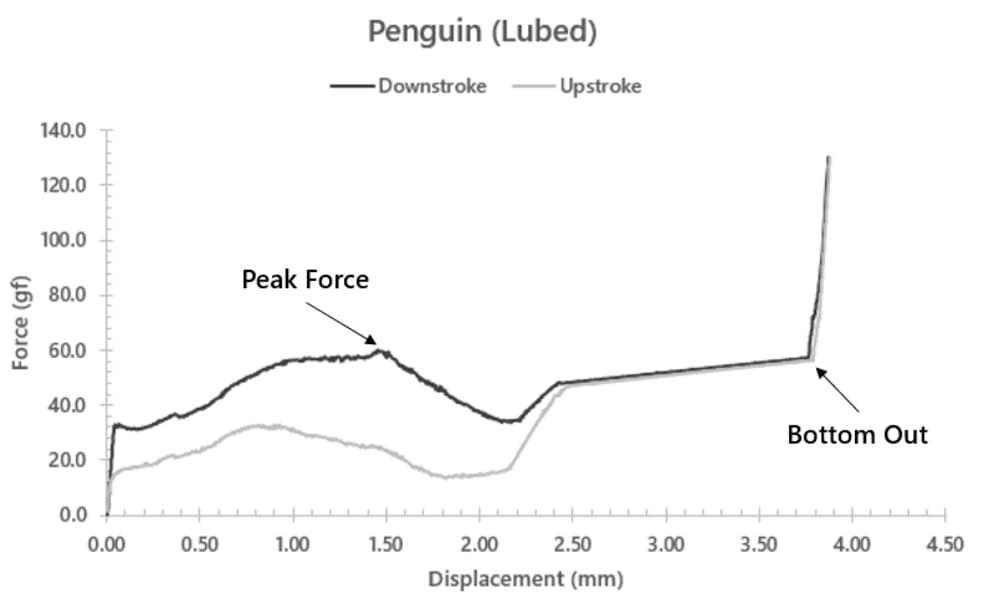

53g Symmetric Springs

Before we briefly touch on the different types of springs out there and what you can expect of them, it’s probably best to know the basics of how switches are marketed and sold. In addition to coming pre-installed in stock switches, springs are often times sold separately by vendors with the explicit goal of exchanging them for springs currently within switches. Regardless of the type of spring that you’re purchasing, almost all of them are marketed or categorized by their weighting – either at ‘bottom out’ or ‘actuation’. As both of these names directly imply, these weights are the force that your switch would push back on your fingers with when it is pressed all the way in (bottom out) or when it has been pressed in just far enough to cause your keyboard to register a stroke (actuation). Given that actuation distance is a function not only of the spring but the leaf, stem, and internal design structure of any particular switch in and of itself, its highly encouraged that you consider just the bottoming out weight when making your purchasing choices as this is consistent regardless of those other factors. An additional point to consider is that tactile switches will also have a third, switch-dependent weight that isn’t marketed called its ‘peak force’. Since the stems and leaves in a tactile switch interact and produce directional forces which are not perfectly up and down in the direction of the spring compression, this leads to a tactile bump which requires a force to push past it that is different than the actuation or bottom out force.

Force curve diagram for Kinetic Labs Penguins

With this knowledge in mind that is applicable to all types of springs, lets take a consideration of the three most common types of springs that you’ll encounter in switches today:

‘Basic’ Switch Springs

Switches with 'basic' springs: Cherry MX Red, KTT Mint, Gecko Silent Linear

The most ubiquitous of all keyboard switch springs, these simple helical springs have been around since the very first days of Cherry MX switches and will almost certainly outlast any other boutique spring type that has cropped up over the years. Obeying Hooke’s Law, these simple springs produce a force which is directly proportional to (a spring constant and) the distance the spring is pressed in. In true linear switches, this is what gives that namesake “linear” feeling – with the force steadily increasing as you press a switch in until the point of bottom out. Coming in a wide variety of lengths, materials such as steel, gold, etc., and thread per inch counts as well, there’s not all that much solid information out there directly comparing how each of these various features of springs plays a direct role in the overall push feeling of a switch. Even as someone who is extremely into collecting switches and learning everything I can about them, much of my understanding of the differences between these features is purely a function of second-hand, loosely tested knowledge. One thing I do know for certain, though, is that while Box switches, CAP switches, Alps switches, and many traditional MX-style switches all use basic, cylindrical springs, they are not interchangeable with each other, so do not make this mistake when planning out your next frankenswitches!

Multi-stage’ Switch Springs

Switches with multi-stage springs: Gateron Pro 2.0 Silver, Neopolitan Ice Cream, Husky Linear

The second most common type of spring that you will encounter in custom keyboard switches are what are known as ‘multi-stage’ springs. Shaped like a cylinder similar to basic springs, multi-stage springs have variable threading throughout their length which produces differing regions of more tightly wound and more loosely wound spring. When compressing a multi-stage spring with two or even three stages, it is believed that this can produce a ‘progressive’ type feeling in a switch, in which the force increases exponentially as a switch is pressed in further, instead of a constant force increase like in basic springs. Available as aftermarket swappable springs more often than in stock switches, most progressive springs are also significantly longer than their basic siblings.

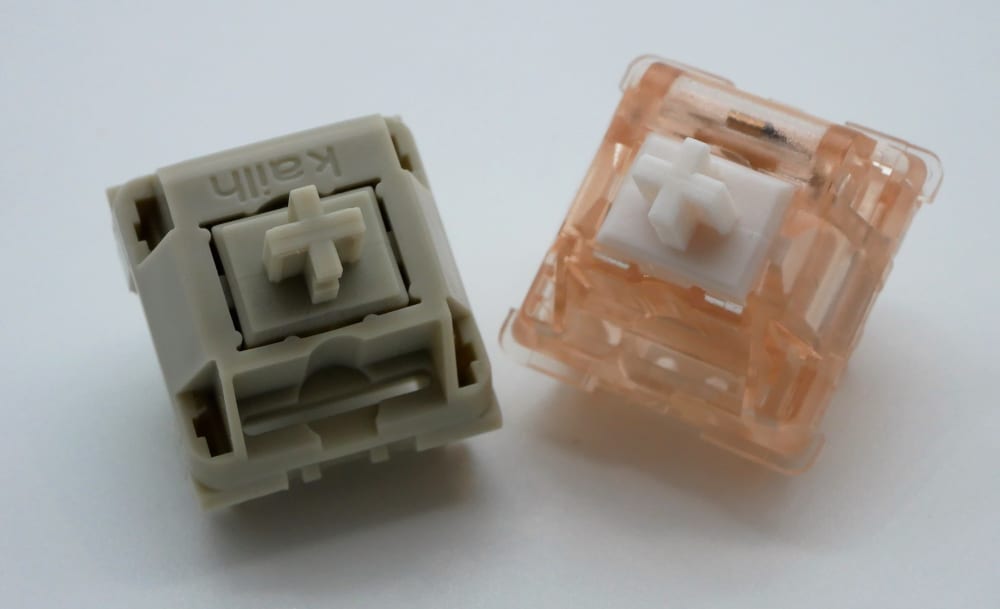

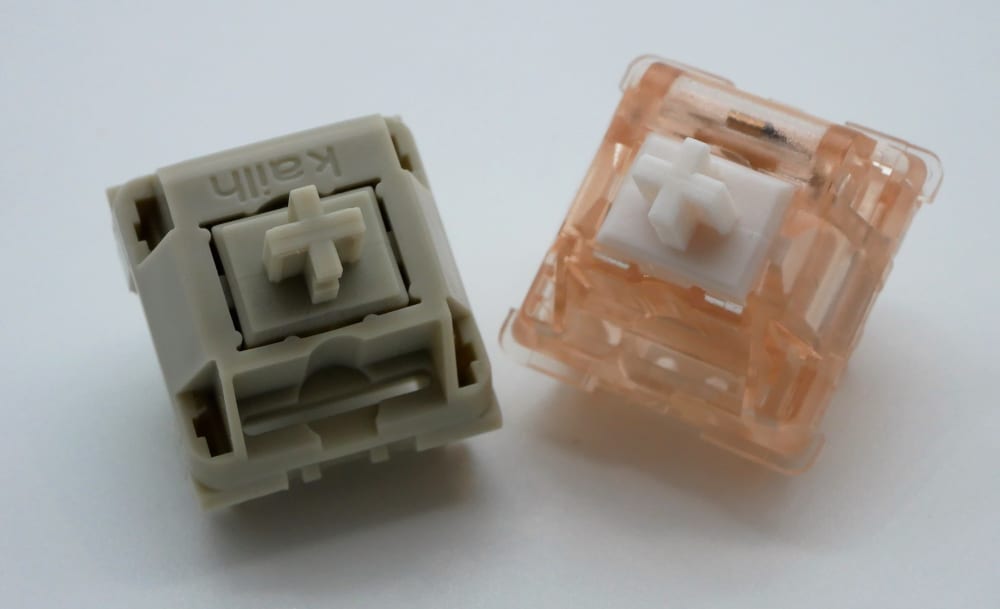

‘Conical’ Switch Springs

Switches with canonica lsprings: Novelkeys Arc Cream and Quartz

The least common but most recently developed type of modern mechanical keyboard switch spring is that of the ‘conical’ shaped. Whereas multi-stage springs have variable threading throughout the length of their cylindrical design, conical springs both have a variable threading and diameter of spring coil throughout the switch. While currently only designed in a singular direction, conical springs flair outwards and increase in their size from top to bottom, which creates an even stronger progressive type feeling within a switch than multi-stage switches. Currently these are very rarely available on the aftermarket, and have only been seen in a small handful of Tecsee- and Kailh-made switches as can be seen in the photo above.

With this newly found information in mind with respect to the different types of switch springs which you’ll encounter on the open market today, you likely think that you’ll know everything and not be surprised by any point of a sales page. Unfortunately, its so much more complex than that! While we covered the various types of springs here, each one of these come in an entire range of bottom out weights from super lightweight at about 30-40 grams of bottoming out force all the way to super heavyweights which can go well above 100 grams of force. Tack on other variables mentioned above such as spring material and length as well, and you’re destined to have infinitely more options then you had considered at the start of this article. Given that there is no hard science out on the matter quite yet, the only thing I encourage you to do is pick some springs up for yourself and experiment until you find your endgame switch spring!